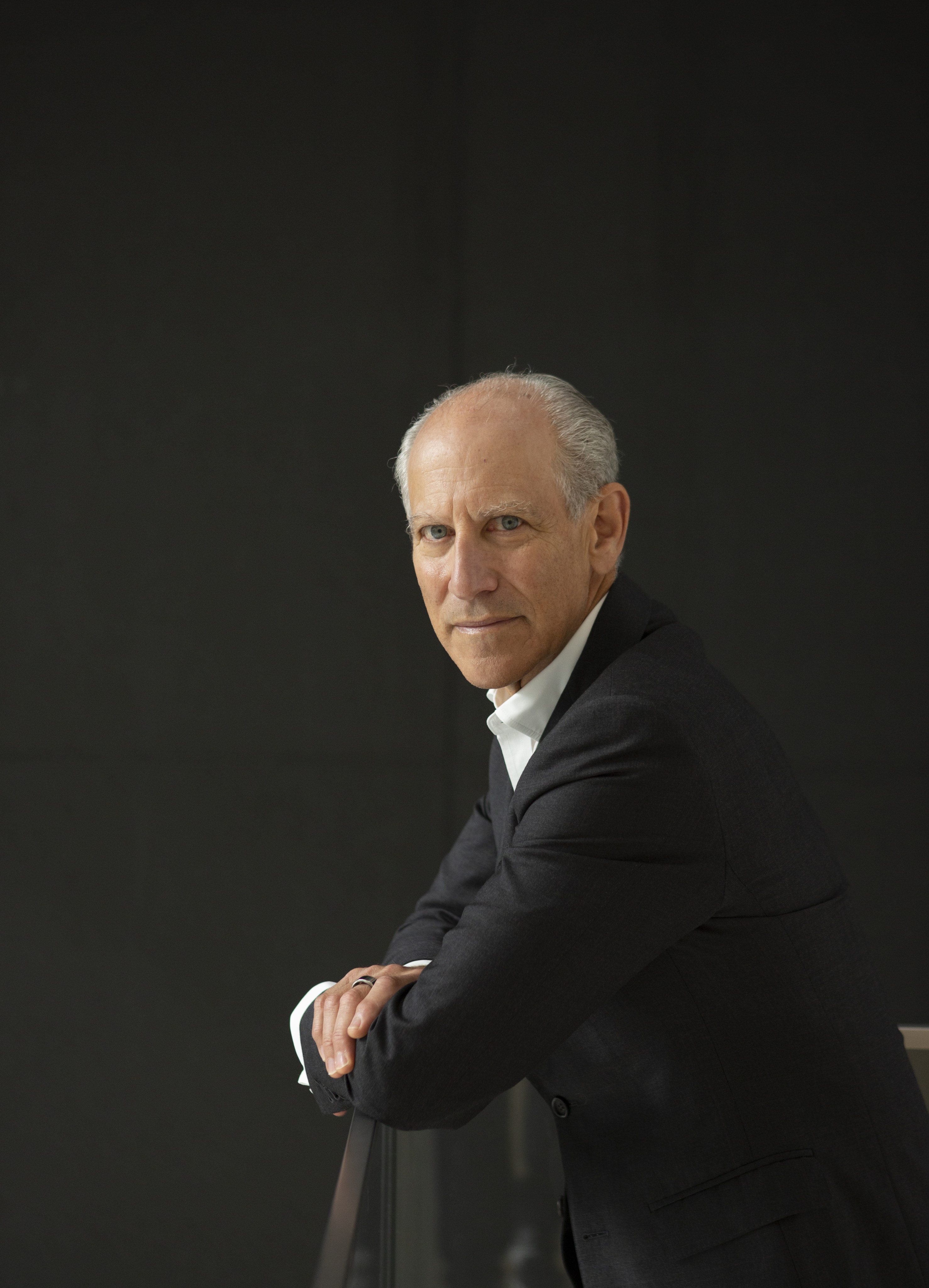

Glenn Lowry, director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art for 30 years, addressed the role of such museums during a visit to Hong Kong’s M+.

Glenn Lowry, director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York for 30 years, visited the M+ museum of visual culture in Hong Kong recently for a meeting with fellow members of the Sigg Prize jury and to deliver a lecture about the future of museums of modern art.

“I love how the museum is completely open to the public,” he said in an interview with the Post. The museum of visual culture in the West Kowloon Cultural District charges for admission, so technically not everyone can walk in to see the exhibitions. But Lowry, who oversees a museum founded in 1929 that is home to Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night and Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, is referring to the absence of security checks.

“I don’t see people with guns. I don’t see people with bomb sniffing dogs. You walk into an American museum today, especially in New York City, and that’s what you’re going to see,” he said.

Lowry, who announced on September 10 that he will retire as head of one of the world’s most famous museums in 2025 after he turns 70, said “everything” changed for MoMA after two members of staff were stabbed in 2022 by an angry member of the public who was denied entry. That was certainly horrifying (the individuals who were stabbed have recovered in large part, Lowry said), but by no means the only attack.

One of the biggest changes at MoMA and many museums in the West has been the growing number of sustained protests and campaigns directed at institutions that were once universally venerated. MoMA has been criticised for its reliance on wealthy patrons, by climate activists and, more recently, by protesters demanding that museums do more to stop Israel’s war in Gaza.

“I like the noise. I like the sense that everybody has an opinion. I think our challenge is to listen, to absorb what is important and relevant, and to understand how to deal with what isn’t,” Lowry said. “The messiness of differing opinions and of all the things that can make a museum’s life difficult can be really aggravating. But I wouldn’t have it any other way, because out of that aggravation comes energy, comes knowledge and comes the ability to work with people of differing opinions.”

Lowry has made big changes at MoMA, including the museum’s 1999 merger with PS1, a contemporary art institution in Queens, New York, two major expansions and increasing the all-important endowment at the privately funded institution from around US$200 million when he joined to US$1.7 billion.

Having brought in a new generation of curators with very different perspectives, he also hopes that he has fundamentally expanded the intellectual parameters of what used to be a European- and American-centric museum, and engaged MoMA in a global conversation. A recent solo exhibition at MoMA PS1 of the work of the late Filipino-American fabric artist Pacita Abad is a case in point, said Lowry, whose own speciality is Islamic art.

His world view is what has led him to M+, where he and fellow judges would decide on the shortlist for the 2024 Sigg Prize, which is open to artists born or working in the Greater China region.

The three-year-old museum in Hong Kong is “precisely the kind of institution that many of us have been dreaming of, a large, gifted organisation grounded in Asia with a global perspective”, he said.

Just as MoMA has been under attack, M+, too, has faced its share of criticism, including from politicians who want to see the museum censor any art critical of China. To Lowry, that makes the museum more interesting, and important.

“I think that M+, as a window on the world, as a place where difficult, competing, contradictory ideas can be encountered and where the voice of the artist, largely unfiltered, is still present, has its own importance. And maybe that importance is even greater at a time of precarity. Tension, while it exists, tends to be very productive,” Lowry said.

He expanded on the idea of an imagined, global museum in his M+ Lars Nittve Keynote Lecture at the museum’s Grand Stair on September 14, attended by hundreds of members of the public as well as fellow Sigg Prize judges including Maria Balshaw, director of the Tate in London, and the artist Xu Bing.

The risk at a museum like MoMA, which has an enormous collection of 200,000 objects but only gets to show a tiny percentage to the public, is stasis that comes with too strong an attachment to the past, he said.

“Although I know what the solution is, it is simply that nobody will do it. The solution is to have the courage to walk away from all those great paintings, all those great objects that predate you, and have enough confidence that the future will be as interesting in the past,” he said.

And a core belief that has to be dropped is that of an art historical canon, he added.

“I think a museum of modern art is interesting precisely because it’s a work in progress, because it doesn’t know the answers.” If a museum does not live in the present but just in the past, it creates canons, or fixed ideas of what is important.

“Explode the canon,” he urged.

For Suhanya Raffel, director of M+, the canon is still necessary, especially for the field of Asian visual culture which has a far less rigid sense of historical hierarchy.

“We do need to have histories that are understood like veins in a body, to be recognisable. You also have to recognise that they are multiple, plural and in parallel,” she said during a discussion after Lowry’s lecture.

“Canons are convenient. They provide a scaffold to understand things, but they are also very limiting,” Lowry replied.

Instead, he advocated an approach more akin to the idea of drifting archipelagos, with no sense of hierarchy.

“Trying to move away from the absoluteness of a canon or canons, especially when you’re dealing with the art of the present, just seems to me that it offers us a kind of liberating dimension.”

Enid Tsui