On time and under budget? The St. Louis Symphony Orchestra has a lot to cheer about with the expanded Powell Hall.

Benjamin Torbert Special to the Post-Dispatch

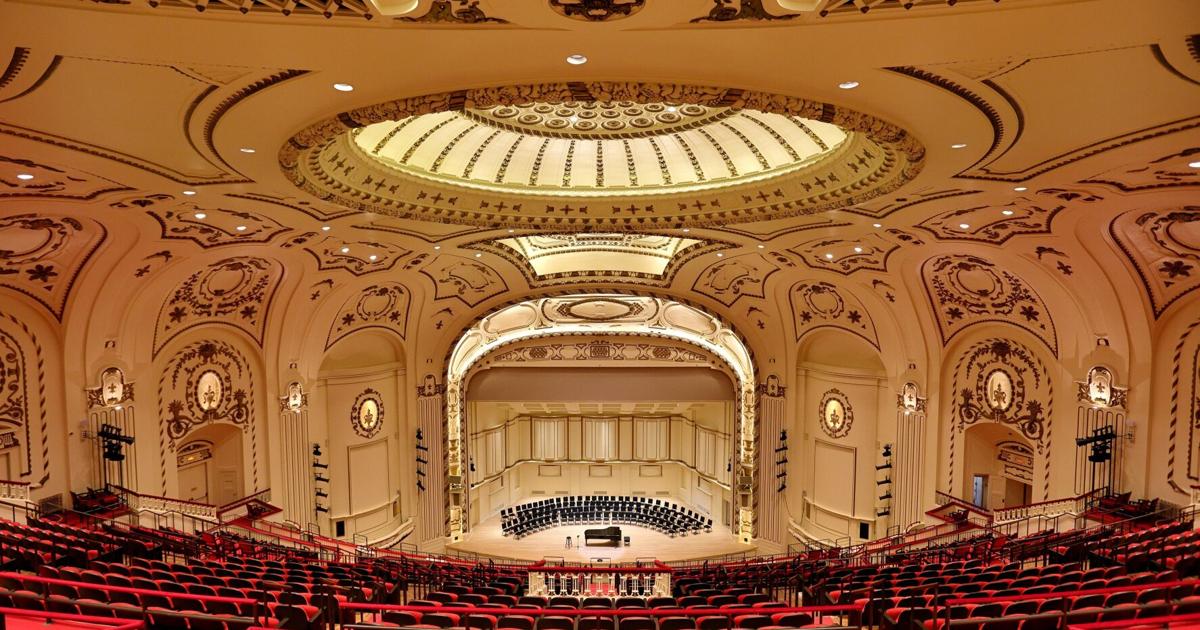

One of St. Louis’ grandest dames, Powell Hall, reaches her hundredth birthday, looking better than ever. After a decade of planning and a two-year, $140 million renovation, the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra reopens its home on Sept. 26 with “Opening Weekend: A Fanfare for Powell Hall.”

The project refurbished Powell by removing older small seats in favor of new larger ones; adding bathrooms and concession areas; and erecting the Jack C. Taylor Music Center, a 64,000-square-foot expansion with space for staff, rehearsals, education and a new box office.

Dignitaries, led by SLSO President and CEO Marie-Hélène Bernard, snipped the ceremonial ribbon on Sept. 19 and announced that the campaign for the renovation had raised $173 million, the largest fundraising haul in SLSO’s history.

The surplus funds will be added to the endowment for facility upkeep.

“This is more than a building, it’s a promise to our city, our artists, and the future of the St. Louis region to make music more accessible for all,” Bernard said at the ribbon-cutting.

Powell: From Vaudeville to concert hall

Powell opened for Vaudeville and motion pictures on Thanksgiving Eve, 1925. Its history of unamplified music begins then; remember, those movies were silent, accompanied by live music.

A century later, Powell’s main occupant is experiencing a golden age. Nearing its sesquicentennial, the SLSO has reached fiscal security. Bernard’s homerun hire of Music Director Stéphane Denève in 2017 reinforced the orchestra artistically after David Robertson’s 2018 departure.

But when Bernard arrived in 2014, though she loved both city and organization, much of the building didn’t impress. “It was no longer supporting the needs of audiences in the 21st century.”

People elongated, and seating constricted. Crowd flow through the tight foyer clogged during sellouts. Queueing for bars occurred nearly atop one’s neighbors. Post-imbibing, one encountered claustrophobic restrooms. Backstage operations faced similar challenges. Powell needed some help.

Movement will become easier. Says Bernard, “ADA compliance was really important. We wanted to make sure to make the hall more accessible to those who have mobility issues or special needs.”

And on Instagram, the 6-foot-5-inch Denève luxuriates in the legroom of a new seat.

Bernard envisioned the renovation as contributing to the orchestra’s long-term future. “Part of my role is to always anticipate six months, two years, five, 10, 25, a hundred years from now. So how do you shape the orchestra of tomorrow? And how is the facility supporting your artistic aspiration? And how do you serve a community?”

To support artistry, one cannot mess indiscriminately with a concert hall. In the SLSO’s two seasons on the road, they enjoyed golden acoustics at University of Missouri–St. Louis’ Touhill Center. But concerts at the Stifel Theatre (the orchestra’s old home from 1934-68), where pendulous curtains devour sound and no bandshell surrounds the band, contrasted Powell.

“In a place like Stifel, we have to learn to create more resonance on stage, but in Powell, we don’t have to work at that,” says principal oboist Jelena Dirks. “Playing in Powell, there’s just a natural singing quality to the hall itself. I just adore it.”

Bernard assures they prioritized preserving — even improving — Powell’s acoustics. “We would not have harmed the acoustics. Part of the mandate with the architects and the acousticians initially was to ensure that we addressed acoustic issues that the orchestra experienced onstage.”

A four-number concert at the ribbon-cutting, featuring a John Williams fanfare, demonstrated astonishing acoustic vibrance. Denève encouraged attendees to return and to listen from the last row in the balcony, 170 feet from his podium.

Backstage, musicians too will move more easily. While praising the acoustics, the beauty of the hall, and “the grandeur of the Versailles-esque hallway,” Denève reports “everything else was really a problem. When we had concerts with chorus, it was mayhem over there. There was just no space for people.”

Principal Horn Roger Kaza notes the reno serves gender equity. “The demographics when they built it were overwhelmingly male. We had this huge dressing room in the basement, and you had to share one of the lockers. Then the handful of women were upstairs, just wherever they could find some space. That’s completely changed.” The expansion augmented dressing quarters for an orchestra now rostering more women than men.

Too, Denève enthuses at the construction of the new Taylor Center and its arching south entrance. “It was an incredible opportunity to do more and especially to create also a new space, which is very dear to my heart, the Education and Learning Center. We have this new space where in parallel with the rehearsals, we will have events and welcome young people.”

Opening fanfares

The orchestra’s artistic excellence provides the best welcome possible on opening weekend. The first public concert in the venue will feature two world premieres.

The three opening weekend concerts all feature the same program and open with a loose triptych of fanfares, all newer than Powell. Aaron Copland’s ubiquitous “Fanfare for the Common Man” requires little introduction. Michael Jackson, the Chicago Blackhawks and others have sampled it. Joan Tower wrote six responses to Copland called “Fanfares for the Uncommon Woman;” the orchestra will play No. 1 for the first time.

The first of two world premieres completes the fanfares. Prolific Michigan native and composer James Lee III offers “Fanfare for Universal Hope,” among seven new works he unveils at major orchestras and chamber groups in 2025-26.

Anchoring the first half of the concert, prominent mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato sings “House of Tomorrow” by Kevin Puts. DiDonato played Virginia Woolf in Puts’ opera “The Hours,” staged by the Metropolitan Opera in 2022 and 2024.

Surprisingly, the Kansan DiDonato debuts not only with the SLSO, but in St. Louis overall. “As a Kansas City native, it is true that I’ve favored the western side of the state, but I have long wanted to join this historic symphony, and I can’t begin to imagine a better moment!”

DiDonato loves performing Puts’ music. “It is truly a gift to sing the music that Kevin has written for me. This is now our third collaboration and it’s clear that he understands and loves the voice in a way that can tell the story and convey the emotion at hand. We talk a lot about the score, and he remains incredibly open to adjusting or taking on board ideas that I might throw out at him. His writing is so evocative, and he sets the text so well.”

SLSO Chorusmaster Erin Freeman, whose group acts as a dialogic Greek chorus in the piece, praises the music and the text, which is from Kahlil Gibran’s “The Prophet.” “It’s quite a beautiful text and (Puts) writes so astutely for the voice. It feels very natural, although I can sense the cleverness in it as well.”

Puts read the line, “But you shall not be trapped nor tamed. For your souls dwell in the house of tomorrow,” and he thought of Powell.

“I imagined the new Powell Hall very much as a concert ‘house of tomorrow.’ When I read Gibran’s entire text, I found many sections that I thought could work very beautifully when sung. I could imagine Joyce (DiDonato) as the prophet, and a chorus as the townspeople who first ask her to expound on various subjects and then repeat her answers in contrapuntal textures as she sings them.”

Puts, of St. Louis nativity, expresses affection for his collaborators, and excitement at the occasion. “This commission is very meaningful for me, and I wanted to do something that serves the occasion well. Joyce teaches me things I didn’t know about my music. And that is a revelation, over and over again, with each project.”

After intermission, Denève conducts Richard Strauss’ symphonic poem “Ein Heldenleben” (“A Hero’s Life,” from 1898), an epic work employing massive, hall-filling orchestral forces, testing those spruced acoustics.

Approaching Powell’s second century, Denève celebrates the power of orchestral music. “It’s alchemical. With an orchestra, you can do anything. We know now that to suggest (outer) space, thanks to John Williams, we need a symphony orchestra. To express a world without sound, we use a symphony orchestra. And somehow I’m so privileged to be part of this achievement of humanity, which is an orchestra.

“When people think, oh, this may die, no. I am absolutely sure that if we have the luck to meet each other in 500 years, this world will have a symphony orchestra. In 500 years, human beings will be moved to look at the starry sky and say, ‘Oh my god, this is so beautiful and metaphysical.’ And I think the orchestra will be the same. There will be an orchestra then.”

And perhaps, Powell Hall will remain too. Its second century looks secure already.