The Critical Case of Patient K. by Aziz Muhamed By Jerina Zaloshnja “Let’s take a family photo,” suggested the prominent Saudi Arabian writer Yusuf ElMuhaimid, author of two of the latest books published in Arabic by Tirana Times (“A Man Chased by Rats” and “The Journey of the Najdi Boy”). It was nearly the end of one of Tirana’s most significant events, the Saudi Arabian Cultural Week (September 17 – 20), after the presentation of our four titles at the event: The Najdi Boy and A Man Chased by Rats by Yusuf ElMuhaimid; The Bursting Tree by Umaima Al-Khamis; and The post A modern writer of Saudi Arabian literature appeared first on Tirana Times.

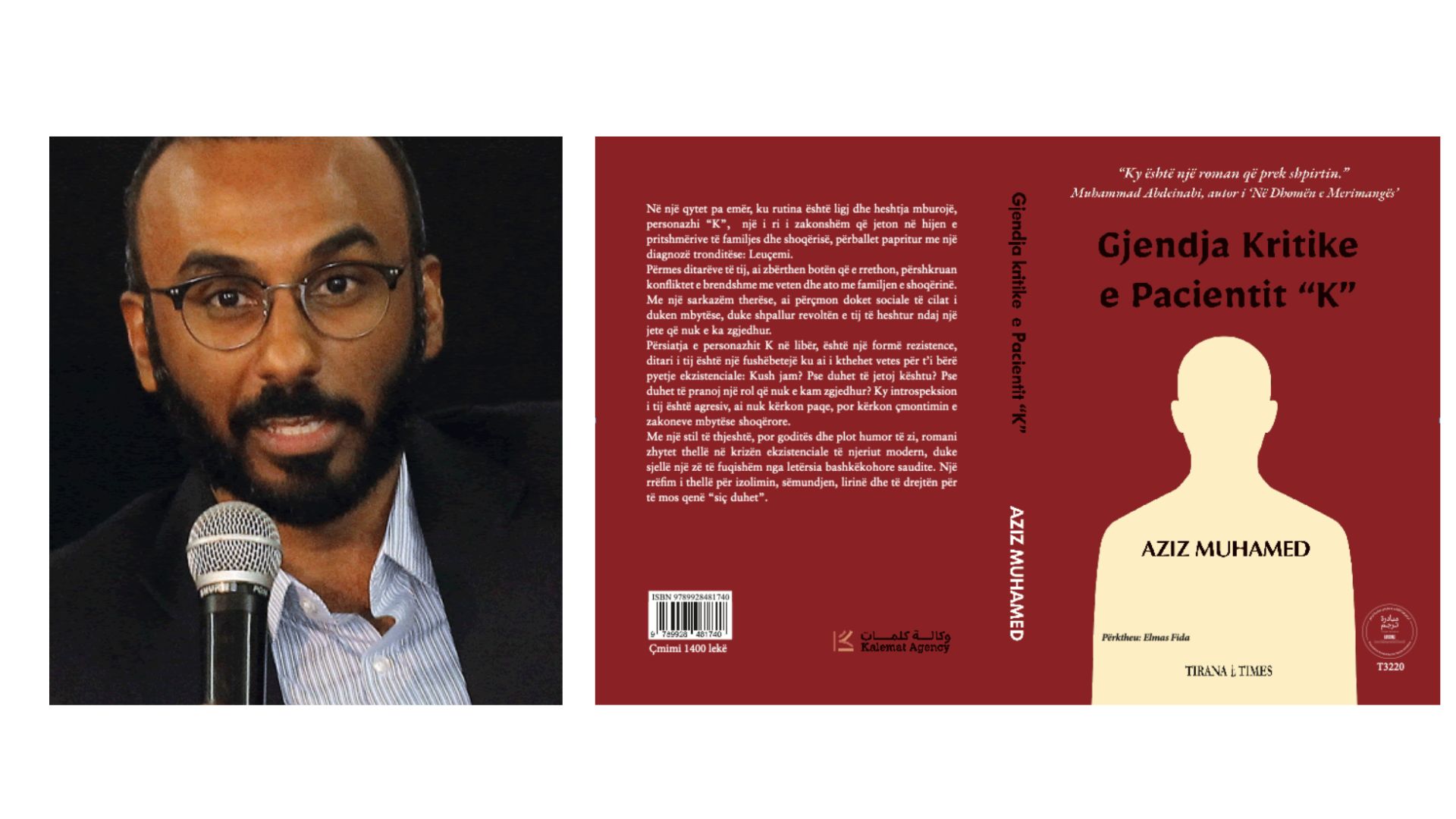

The Critical Case of Patient K. by Aziz Muhamed

By Jerina Zaloshnja

“Let’s take a family photo,” suggested the prominent Saudi Arabian writer Yusuf ElMuhaimid, author of two of the latest books published in Arabic by Tirana Times (“A Man Chased by Rats” and “The Journey of the Najdi Boy”). It was nearly the end of one of Tirana’s most significant events, the Saudi Arabian Cultural Week (September 17 – 20), after the presentation of our four titles at the event: The Najdi Boy and A Man Chased by Rats by Yusuf ElMuhaimid; The Bursting Tree by Umaima Al-Khamis; and The Critical Condition of Patient K by Aziz Muhamed. After days filled with panels, discussions, music, dates, culinary delights, and countless activities, it truly was the perfect moment for a photo.

We all gathered around ElMuhaimid, one of contemporary Saudi Arabia’s literary giants, who exuded the presence of a dignified and attentive host: myself; Dalal NsrAllah from the agency Kalamat based in Riyadh, without whose support our books might never have seen the light of day; translators Elmas Fida and Alban Reli; the Saudi panel moderator; the well-known journalist Ahmed Al Rodaini; and several others.

The translation and publication into Albanian of modern Saudi literature is a strategic project and still in its first steps, but it has been very well received in Albania.

At the very end of the row, in the corner, where the photo might capture him – or might not – stood a young man of modest height, with a timid gaze.“Who are you?” I asked.“My name is Aziz Muhamed,” he replied.

I had found him! Aziz Muhamed, the modern voice of contemporary Saudi literature, was perhaps the hidden and most compelling reason for my presence there.

I had read his first – and so far only – book, The Critical Condition of Patient K, in English a few months earlier, and from the opening pages, I sensed I might be encountering a new Franz Kafka: domineering, moaning, despairing to the last drop – the mildest terms I could use. Being among those for whom suffering is part of existence, I thought: I have found it! This book was for me.

Without prompting, I immersed myself in translating it, sometimes revisiting passages with admiration, sometimes “whispering in the author’s ear” for him to step back, to take distance from his idol K, to find his own path – which lay right before his eyes, but could he see it? I experienced the translation process so intensely in this “incognito” mode that it hit me like a bomb when I was informed the book would be translated from the original, as it should be. Naturally, I stepped back, but I eagerly awaited to see Elmas Fida’s finished translation for comparison.

When I did, I had to take a step back in awe. The translation from the original remained unparalleled, and, moreover, the translator demonstrated a profound closeness to the pain embedded in the text – a necessary condition, in my view, to fully understand the book.

Unable to append my name alongside that of the most modern Saudi writer, I asked Mr. Muhamed for an interview.

“All right,” he answered.

A REASON TO LIVE

Q&A with Aziz Muhamed, the author of “The Critical Case of Patient K

Q: Why do you write, Aziz Muhamed? When did you first realize that writing was within you?

A: I have a love-hate relationship with writing. On the one hand I hate its hardships and demands, especially as someone who can only write in solitude, so I keep a certain distance from it, closer to a distance of necessity. On the other hand I define myself as a writer, a label I don’t feel I fully belong to because of that distance. Yet many times I have found in writing a reason to live, so I owe it a lot of gratitude for having saved me from a life that might have been empty without it, or might not have existed at all. This happened for the first time during a period of depression in my adolescence. I realized then that I would always have this refuge if nothing else could pull me out.

Q: From your novel The Critical Case of “K”, it seems you are deeply connected to pain. In this book, you did not miss a single nuance in depicting it; one might say you took suffering by the hand. How did the idea for this novel come to you? Why did you choose to portray it in such a visceral, specific manner?

A: In some of my earlier stories, I was preoccupied with the dread of death, and this time I wanted to write something different. I wanted to write about someone who, although approaching death, does not seem to be concerned by it. As a result, the word “death” is hardly ever mentioned in his diary, except sarcastically. This visceral manner of depicting the illness seems to be K.’s way of keeping himself occupied, and finding meaning in his suffering, because in the end he is intent on turning his diary into a literary work, in the spirit of his favorite writers who transformed their suffering into works of value. So the question for me was: how far can I go in making his depiction of his illness feel real and tangible, without losing its literariness?

Q: Did you struggle much with this novel? How long did it take you to write it? Did you anticipate the public’s reaction? Were you intimidated by the sudden popularity, or were you already aware that you had written such an important book for the literature of your country – and beyond?

A: It took me a year and a half to complete, which now feels brief compared to the five years I spent on my second novel. By the time I began writing The Critical Case of K., I already had a clear sense of the effect I wanted to achieve. I was conscious that the theme of cancer might make the book popular and the protagonist easy to gain sympathy, so I deliberately made the him less likable. To my surprise, however, this very unlikability ended up making his story more memorable among many readers.

Q: Your style is dense, sharp, yet also imbued with a kind of intimacy rarely found in modern Arabic prose. Which writers from the East or the West do you admire?

A: I would not say this intimacy is rarely found in modern Arabic prose. It is in fact so common that I am finding it hard to attribute it to just a few names. I owe much of this style to Arabic translators as well, who offered me a new way of approaching classical Arabic with a modern touch, even if their translations were not always faithful. Among them are the Lebanese poet Bassam Hajjar, Rose Makhlouf, Munir Baalbaki, Ibrahim Watfi, and others. Of course, I was influenced by all the writers mentioned in the novel, but it is important to note that the narrator in my book is someone shaped by translated literature, which he sees as an escape from his circumstances. I might have to choose a different style with a different narrator.

Q: Do you see yourself as a “solitary flower” in your country’s contemporary literature? Are there other writers who, like you, distance themselves from the traditional forms of Arabic literature? Could you mention some names?

A: I don’t think we can fit traditional Arabic literature into a single mold, especially since even my own novel is not entirely detached from its preceding heritage. Again, I should stress that we need to distinguish between the narrator’s perspective and the work itself. The alienation felt by the narrator suggests a break from all tradition, but perhaps we shouldn’t always believe his word. There are many new voices in the Saudi literary scene with fascinating relationships to traditional literature. The novels and stories of Ahmed Al-Huqail, for instance, are deeply rooted in traditional arabic literature, some might even trace back their style of Al-Jahiz and the Arabic prose writers of the 4th century AH. At the same time, I am not sure his writing would be the same without the influence of W. G. Sebald.

Q:What are you working on now?

A: I recently published my second novel, Intimate Strangers, which follows the story of an architect in Eastern Saudi Arabia, ten years after his sister’s escape abroad; an event that continues to haunt him as he tries to reconnect with his homeland through traditional building practices, all while growing increasingly paranoid that his wife might follow in his sister’s footsteps. I’ve already begun work on a third novel, which may turn out to be interlinked with this story. Aside from literature, I work as a screenwriter for films and TV series, mostly on the commercial side so far, but they are a lot of fun and I find them very rewarding creatively, and financially of course.ide so far, but they are a lot of fun and I find them very rewarding creatively, and financially of course.