In the midst of rebellion, Prince Salim’s portrait of Humayun became a powerful tool in crafting his own legacy, distinct from his father Akbar.

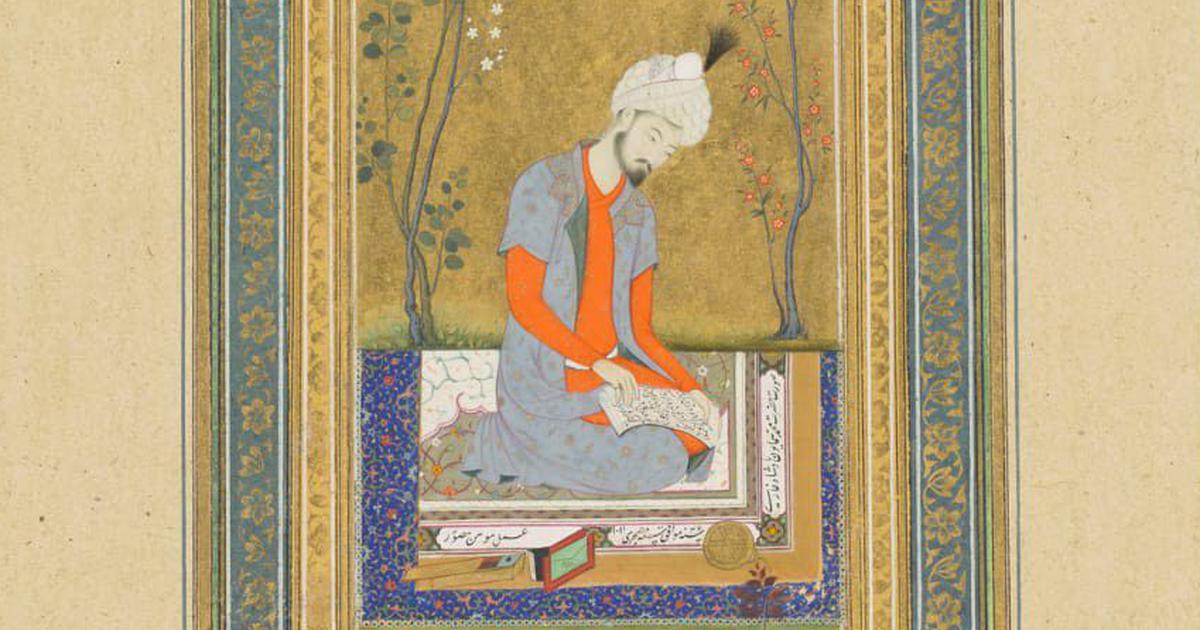

In 1603, Shahzada Salim, the future Badshah Jahangir, commissioned a curious portrait. In it, his grandfather, the second Mughal Badshah Humayun, kneels on a richly patterned blue carpet, reading a poem by the 13th-century Persian poet Sa’di. The verse is from a collection titled Bustan or Fragrant Garden, mirroring the dreamlike, classical Iranian paradise in which Humayun seems to be seated.

A number of objects are placed next to him bespeaking his well-documented cerebral nature – an open pen-box, manuscript, portfolio and, on the right, a metal disc relieved with the design of a cross: a planispheric astrolabe. The painting, by the artist Mohan, is titled after the instrument – Humayun with astrolabe, a reproduction of which is on view at the Humayun’s Tomb World Heritage Site Museum in New Delhi.

Invented in the ancient Hellenistic world, the astrolabe comprised two components: the rete, which is a two-dimensional projection of the night sky, and the tympan, which is an interchangeable plate, calibrated for a specific latitude, that sits atop the rete and is marked by lines indicating height above the horizon and direction.

Used for measuring the altitude of celestial bodies above the horizon, the astrolabe lent itself to a variety of related purposes: determining their positions, calculating latitudes for terrestrial navigation and determining local time. Finding its way to Arab lands in the 8th century, where it was dubbed al-asturlab, the instrument became an important locus of the Islamic culture of science and technology.

In Akbarnama, Abu’l Fazl praised his subject’s father, Humayun, as “alidade of the astrolabe of theory and practice”, possibly alluding to his fostering a rich intellectual culture at court. The alidade is a rotating rule on the back of the astrolabe with two sighting holes. The user would align these with the sun by day or a star by night, then read the angle against the degree scale engraved around the back edge. That measurement could then be carried to the front, where the rete was rotated over a tympan calibrated for the local latitude, forming a map of the current night sky through its delicate metal filigree. In this way, the heavens could be cast and held in the palm of one’s hand – a fitting conceit for a Great Mughal to indulge.

Keeping in mind the instrument’s function as cosmic compass and celestial plotter, Humayun with astrolabe seems – in the vein of Jahangiri iconography articulating “ideal kingship” – to represent the badshah as a sovereign who presides over the heavens. Yet, no other Mughal badshah seems to have been depicted with an astrolabe, making the instrument’s presence in the painting more than just another of Jahangir’s usual allegorical flourishes. It points to both Humayun’s real intellectual interests and to a personal link between two Mughals who stood, through circumstances of exile or rebellion, outside of the imperial centre.

Recurring motif

What might we speculate about the design and form of the obscure astrolabe lying in a corner of Humayun’s rug?

Science historian Sriramula Rajeswara Sarma writes in his 1994 essay The Lahore Family of Astrolabists and their Ouvrage that the earliest known extant astrolabes in the subcontinent are connected to Humayun. They were all crafted by a single Lahore-based family, the patriarch of which served as the royal astrolabist to the second Mughal. Two astrolabes signed by the dynasty’s paterfamilias Ustad Allahdad Astarlubi Lahuri survive: a 1567 specimen at Hyderabad’s Salar Jung Museum and a 1570 one at Oxford’s History of Science Museum. Both, Sarma notes, exemplify a style influenced by Safavid design but distinctive to India.

Two features stand out: a high kursi or throne, that is the triangular structure that connects the astrolabe’s body to the suspension ring (solid in the Hyderabad astrolabe and pierced in the Oxford one), and the intricate tracery on the rete (with tiger claws in the former and floral and avian arabesques in the latter). Together, these elements reveal an Indo-Persian aesthetic that the Oxford astrolabe would later help consolidate for future generations.

On the inner side of the thick, hollow, high-rimmed disc containing both rete and tympan are “a geographical gazetteer, containing the names of cities, their latitudes, longitudes, inhiraf [angle of deviation from the direction of Kaaba] and the duration of the longest day”. Among the largely West and Central Asian cities are a few Indian ones as well, though ironically not Lahore.

While these instruments postdate Humayun’s death, Sarma argues that Allahdad likely produced others during the emperor’s lifetime. His role as Humayun’s asturlabi is underscored by his son Isa’s adoption of the epithet “Humayuni”, a convention continued by their descendants – as a way to “commemorate the royal patronage extended to their ancestor”. Another astrolabe on view at the Humayun’s Tomb World Heritage Site Museum – this one outside of a painting – was also made for Jahangir by Isa’s son and Allahdad’s grandson Muhammad Muqim ‘Humayuni’.

Despite this multigenerational lineage at the Mughal court, Sarma observes in his 1992 essay Astronomical Instruments in Mughal Miniatures that the planispheric astrolabe can be seen in only two paintings: an Akbari interpretation of Noah’s Ark (1590) attributed to Miskin and another by Shah Jahan’s painter Govardhan, Astrologer and Holy Men (1650). Humayun with astrolabe seems to be at least one more.

Indeed, the apparatus is a recurring motif in accounts of him. In his biography Humayun-nama, penned by his sister Gulbadan Bano, is the story of how, after ensuring that his future empress consort and Akbar’s mother Hamida Banu Begum was persuaded to marry him, he “took the astrolabe into his own blessed hand” and chose a propitious hour for the wedding. In Tarikh-i-Humayun, an account by Bayazid Bayat, there is an anecdote wherein he made a show of using an astrolabe to determine the favourable hour to pursue a rebel he secretly wanted to let flee. The natal chart of his son Akbar was prepared at Amarkot by Humayun’s Hindu astrologer Maulana Chand, whom Abu’l Fazl describes in Akbarnama as “possessed of great acuteness and thorough dexterity in the science of the astrolabe”.

Scientific passion

While much has been written about the Mughal interest in astrology, art historian Ebba Koch, in her book The Planetary King: Humayun Padshah Inventor and Visionary on the Mughal Throne, instead draws attention to how Timurid interest in ‘ilm al-hay’a or planetary theory also produced curiosity about the science of astronomy and “brought with them attention for geometry, trigonometry and arithmetic as the tools needed for calculating horoscopes and developing planetary models”.

At various times and places, Humayun’s court was populated with serious astronomer-mathematicians. In fact, as historian Ali Anooshahr has argued in his essay Science at the court of the cosmocrat: Mughal India, 1531-56, he patronised astronomy over astrology, a distinction that “helps explain the prominence of what we would call cosmological factors in the textual productions of Humayun’s court”. Referencing the writings of a number of scholars at his darbar, Anooshahr reveals a blending of Ptolemaic and Islamic cosmologies in the work of both Indian and immigrant scholars “had something to do with the intellectual atmosphere” of the Humayuni darbar.

Appropriately for a king presiding over such an atmosphere, Humayun himself wrote texts on science and mathematics, even planning to build an observatory before his fall from the library steps in 1556. Was the painting commissioned by Salim almost half a century later a simple exaltation by a royal grandson of his late grandfather’s erudition? In the vein of Jahangir’s famous allegorical paintings featuring another premodern scientific instrument, the terrestrial globe, the astrolabe emphasises Humayun’s omniscience and cosmic majesty. But there are other layers to its presence.

In her essay Two Late Mughal Albums in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle: Further Evidence for the Collections of Nawab Asaf al-Dawlah, curator Emily Hannam locates the original Humayun with astrolabe in a 58-folio album belonging to the 18th-century Nawab Wazir Asaf ud-Daulah of Awadh. It is part of “a set of six portraits… painted for Prince Salim…during his period of rebellion against Emperor Akbar, when he set up a semi-independent court in the city of Allahabad”.

In her book Real Birds in Imagined Gardens, art historian Kavita Singh expounds on a “rebel aesthetic for a rebel prince”: having installed his own court in defiance of Badshah Akbar, Shahzada Salim also set up a parallel Mughal atelier. Challenging Akbar’s authority not just politically but culturally, Singh contends that Salim’s “aesthetic choice…was dictated by the need to forge a cultural identity distinct from Akbar’s imperial center…to claim a lineage that legitimized his kingship yet bypassed his father”. For this, he turned to his grandfather Humayun.

Many of Salim’s artists were Persian emigrés, an echo of Humayan’s patronage of the two Safavid miniaturists he brought back from Shah Tahmasp’s court, an act that resulted in a new subcontinental miniature tradition. In Humayun with astrolabe, the subject’s seat in a classical Iranian garden, and the “abstract sense of space allows the viewer to situate the deceased Emperor in an imagined, non-temporal, paradisiacal realm”, according to the Royal Collections Trust’s own note. But the mystical quality of the portrait is not just a result of Humayun’s pious, fakir-like kneeling pose, but the deliberately anachronistic Safavid style meant to strategically quote Humayuni painting, a way to validate his claim to Mughal kingship athwart Akbar’s.

Along these lines, a strand of inheritance that Jahangir could potentially draw on through the astrolabe was the scientific passion he shared with Humayun. Quoting Jahangir’s memoir, Koch writes that he “was proud to own a manuscript by his grandfather that contained ‘an introduction to the science of astronomy and some other unusual matters, most of which he had experimented with, found to be true and recorded therein’”. Jahangir’s own scientific bent – his practice and persona as an amateur naturalist – has been discussed by Koch in her 2009 essay Jahangir as Francis Bacon’s Ideal of the King as an Observer and Investigator of Nature. Seen in that light, the astrolabe could be seen as another way for Jahangir to link Humayun’s legacy with his own through their dynastic interest in observing and governing the natural world as Mughal emperors.

In this way, the painting pays Jahangir’s tribute to many Humayuns – the jannati badshah, the convenient ancestor and the patron of art and science. But perhaps there is also something beyond the panegyrical at play, a more poignant homage to Humayun the rival sovereign, yet another status he somewhat had in common with Jahangir though on very different terms. Due to his 15-year exile from Hindustan after being defeated by the Pathan Sher Shah Suri, and his untimely death soon after his return, Humayun spent much of his life as an itinerant figure. An emperor without a throne, the stabilising kursi of his astrolabe, which ensured the instrument’s navigational efficacy and reliability, might have braced Badshah Humayun with the steadying comfort of scientific knowledge.

Could we consider perhaps that the cross on his astrolabe is meant to denote the alidade to which Abu’l Fazl compared him? After all, it is the alidade, and the vision it enables, that activates the instrument in the first place – allowing the roaming emperor to set the stars in his sight, take the heavens in hand, and find the ground beneath his feet before charting the course of an empire that would outlast him by centuries.

Kamayani Sharma is an independent writer, researcher and podcaster based in New Delhi. This project was made possible under the Scroll x MMF Arts Writer Grant.