The Order of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago (ORTT) has been awarded to one of this country’s finest citizens—a man born pre-World War II in Cedros, a generation after the end of indentureship.He was academically gifted enough to achieve…

The Order of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago (ORTT) has been awarded to one of this country’s finest citizens—a man born pre-World War II in Cedros, a generation after the end of indentureship.

He was academically gifted enough to achieve a scholarship to study in Scotland, but returned to Trinidad and Tobago to anchor himself and give a lifetime of service in politics, academia and West Indian literature.

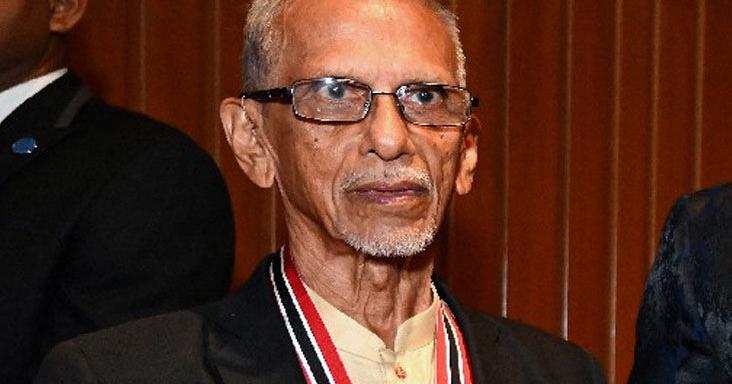

This report is from an interview with Prof Kenneth Ramchand, following his acceptance of the ORTT at the awards ceremony at Queen’s Hall, St Ann’s, on September 24, Republic Day.

One December day in 1983, Samuel Selvon visited the Maracas Valley home of his partner Kenneth Ramchand.

The two decided to drive to Chaguanas to surprise Selvon’s former girlfriend, Kamla. She welcomed them with paratha, tomato choka and bhaigan (as requested by Sam), and sprung a surprise of her own: her brother, Vidia, lounging in the sanctuary of Kamla’s living room, who delighted to tell a story of his arrival at Piarco International Airport from the UK—a taxi driver had recognised him (“you is Naipaul?”) and hustled him protectively into his car because “we doh like you down here at all”.

Before daybreak, the next morning, the three men were heading to Icacos, Cedros, and set off on a pirogue with two engines for Soldado Rock, where the yoga-fit Naipaul, who had invited himself to the lime, outpaced his friends to get to the top, where he offered his thoughts on Venezuela eight miles west.

Back on land, Naipaul stripped down to his jockey shorts for a sea bath before they packed up to head home, but not before the three stopped off at the Gulf City Mall. And that is how two of our finest writers ended up drinking Carib beer with the godfather of West Indian Literature one night in a San Fernando bar.

Of course, many truths were disclosed and many personal matters discussed on those days, including a conversation where Ramchand asked Naipaul, “If you think making love is nothing—friendship is nothing, belief is nothing; if you think life is nothing, why don’t you kill yourself?” To which Naipaul replied, “One has one’s writing.”

It was a perfectly acceptable response, said Ramchand, who will perhaps tell stories like this, “if I ever think it worth writing about my life.”

And what a read it will be, for this legend has 86 years’ stock.

Given his mental and physical vitality, those tales may well extend into a ninth decade.

Cedros: Roots that shaped a life

In his memoirs, Ramchand will detail his early life in Cedros, and how his schooling eventually took him to the University of Edinburgh. Speaking from his Maracas Valley home, he said, “I have not educated myself out of that place. It is so deep in me and has been so formative that I could never emotionally, intellectually, or physically leave it. When I returned in 1975 to settle in Trinidad, it was not just to come home. It was to end all wandering elsewhere, some of which I loved, and to dig back into what was inside me.”

He described a childhood untouched by historical abstractions like indentureship.

“My parents never used that word. They spoke of ‘having a hard time’ or ‘trying to make ends meet’. They had neither shame nor bitter memories. That was a very good thing. We enjoyed our lives: the fish, the coconut trees, the workers, the limers on the seawall, the cows and bulls walking through the village all day. Those things penetrated my consciousness. They didn’t make me want to leave; they made me want to develop and grow,” he said.

Ramchand’s parents had ambitions for him, but never imposed them.

“Early on, someone decided I was next in line after my brother, who went to Naparima College. My mother decided to push me, so instead of sending me to Cedros Government Primary School, I went to a private school run by two old ladies in their living room. It was almost a school within a home. We never got licks; we got shouted at. That school encouraged me to read, to notice, to think, to feel. It didn’t obsess over exams; we were always learning about the world and the people around us. That education was crucial. I kicked so many coconuts up the wide drain leading towards the school to give Miss Jerome to make the sugar-cakes that perfumed our classroom.”

He was the village’s comic-book lover and everybody recognised from his runs up, up, and away that he was Superman.

Later, his mother sent him to Point Fortin Intermediate RC School.

“She had one ambition for me: win a College Exhibition, or come back home and be a fisherman, which was the only ambition I had.”

Santiago was his role model. Ramchand went on to earn a place at Naparima College, twice winning the Best All-Round Student award, and eventually securing a scholarship to study English Literature at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

Academic trailblazer

At Edinburgh, Ramchand pursued a PhD in West Indian Literature, a field virtually unknown at the time.

“Teaching English literature at the university didn’t seem remarkable. I just thought I was good enough to get the job. Only later did I realise Edinburgh was extraordinary: they appointed me, a black man, to teach English Literature to white students, and let me do research on a literature they didn’t even know existed. That struck me years later as something extraordinary,” he said.

His pioneering 1970 book, The West Indian Novel and Its Background, remains central to the study of West Indian literature. Later, his anthology West Indian Narrative introduced Caribbean literature into secondary schools.

His Guardian column, Matters Arising, addressed politics, culture, and current affairs, while he served as an Independent Senator under three successive presidents.

Distinguished lectures included the Eric Williams Memorial Lecture at the Central Bank and the Walter Rodney Memorial Lecture at Warwick University.

Ramchand spoke openly of the writers who shaped his life: “Wilson Harris, Samuel Selvon, Vidia Naipaul, Seepersad Naipaul’s journalism in the Guardian, Michael Anthony, Earl Lovelace, they kept changing my life. I value West Indian literature because these people kept enriching me. Even today, I find insights that help me grow.”

He defined himself as a literary critic with a clear purpose: “While at university, I framed it for myself: I was going to be a different kind of critic. Simple, straightforward. To let people know this literature exists and encourage them to read it, so they could understand why it matters to them as citizens, as human beings. Before I heard of Gramsci I was an organic intellectual. Before I read Edward Said, I lived the immersive life suggested by his phrase ‘the world, the text and the critic’. A little more fanatical than either of them, I think.”

Family and personal life

Kenneth Ramchand met his wife, the elegant Scottish Averil Helen Mackintosh, in a Moral Philosophy class (he sniggered) at Edinburgh University. They married in 1964 at the Church of Scotland. Their children, Gillian—now Professor of Syntax and Semantics at Oxford—and Michael, a senior technical specialist at Oracle, continue the family’s intellectual legacy across Europe and Trinidad. “I’ve always loved my work,” he said. “Sometimes I feel like I’ve been paid to do what I would have done anyway. The pleasure is in reading, thinking, feeling, and sharing these books with young people. No accolade could equal that.”

Preserving the past

Ramchand also played a pivotal role in preserving the Naipaul House at 26 Nepaul Street, St James.

“I saw the advertisement offering it for sale and knew the house—it was immortalised in A House for Mr Biswas. I rang the auctioneer, formed a committee—Friends of Mr Biswas—and we persuaded the government to purchase it,” he recalled. It took some negotiating, but the UNC government minister Daphne Phillips made sure of the acquisition. “Colin Laird, who was appointed chairman, said he would only accept if I agreed to be virtual chairman. Since then, we’ve tried to live up to the mandate: build the Naipaul Museum, create a house of literature for Trinidad and Tobago, set up a library and take our literature out to schools and communities. We do bat on a very unresponsive wicket. You can offer circuses, but you must offer bread as well. Friends of Mr Biswas is now well known, but we’re still working to engage the public.”

Literature, humanity and society

Ramchand believes the humanities are central to societal renewal. “Literature helps us see ourselves in ways that colonial experience would mask as usual. You can talk about crime, but it will never be solved if education doesn’t aim to produce a different kind of person. Much of what is wrong in society exists because we haven’t understood our own humanity. What is it to be human? Those who are responsible for educational policy need to understand that the arts and humanities have a major role to play in the rebirth of society.”

His mission as a critic remains clear: “I want people to know these books exist, to read, feel, and think. Ask yourself: how has this book changed me, my society, my view of the world? That’s my motivation. Everything I’ve written or said has had that intention, to show people these books exist and get them to read them for themselves.”

Life, death, and legacy

At 86, Ramchand reflects on life with a wary equanimity.

“The world is not an easy place. Perhaps our present has become desperate and violent because nobody believes in a future. But there are moments of happiness that feel almost like heaven. Qualities like truth, goodness, sincerity, empathy cannot be cynicised away. Writers and artists keep the dream of wholeness alive. They give us visions that ensure we continue to believe in belief.”

On Trinidad and Tobago today, he is frank: “The colonised mentality didn’t start with enslavement or indentureship; it goes back to genocide and to the near-erasure of our First Peoples, continued through enslavement and indenture, took on new strength under the tutelage of the colonial period. No wonder none but ourselves sabotaged Federation. Since then we have mouthed Caribbean unity and regional cooperation but we have done nothing that might lead to a realisation of the poet’s vision that ‘the unity is submarine’. We haven’t begun to understand the depths in that vision.”

He talks about rebirth and is optimistic about literature’s role.

“My job has always been simple: to let people know these books exist, to remove obstacles so they can read, feel, and think. Literature changes lives; it has changed mine many times over, and it continues to do so.”

On receiving the ORTT, he said, “I have had a quiet sense of accomplishment for a long time. I feel I am doing something in the world that matters to some people, and it makes me happy that it matters. But this comfort, and any accolades don’t make me think I have done my lot. I have to go on. Life is nearly Sisyphean: courage and defiance to push that boulder up the hill. I may never reach the top, but I’m not going to let it roll back on me. It is like the unending struggle of the artist. If anything, the ORTT is a challenge.”